Jorge Luis Borges was deeply inspired by the work of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, whose prints of imaginary prisons and palaces captured the Argentinian author’s imagination.

By: Victor Plahte Tschudi

William Beckford’s short story “Vathek” (1787), according to Jorge Luis Borges, contains the first description in literature of a truly atrocious hell. Beckford wrote of an underground world of endless halls and galleries crowded with people who “each wandered at random unheedful of the rest.” Among the works that influenced Beckford, Borges continues, was Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s “Carceri,” his series of imagined prisons, “depicting mighty palaces which are also inextricable labyrinths.”

“Mighty palaces,” however, form an ensemble grounded less in Piranesi’s prints than in the English essayist and critic Thomas De Quincey’s romantic interpretation of them. De Quincey, with an arresting paragraph on Piranesi published in his drug memoir “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” (1821), largely reinvented Piranesi, pushing the limits of architecture, or, rather, extending its range to include also metaphorical realms; Piranesi emerged as the architect of an entirely new conceptual landscape that spanned hallucinations, dreams, and memories. Piranesi’s disconcerting prisons, recreated as captivating prose, enriched the fields of psychoanalysis, philosophy, poetry, and literary criticism as well as the history of art and architecture. The “Carceri,” on De Quincey’s cue, came to occupy a domain beyond the finite and the rational and provide a scenery — a mental stage set — in a vast and varied literature of introspection from Joyce to Jung, from Baudelaire to Borges.

With the reference to the “Carceri” architecture as palaces — and not prisons — Borges, who was a student of English Romantic literature, inscribes himself into a tradition of literary emulations of Piranesi’s images.

“I met Piranesi through Thomas de Quincey,” Borges admitted in an interview a few years before he died. And although he also came to know the etcher through his prints, it was De Quincey’s visionary retelling of them as dreams that arguably secured Piranesi’s influence on Borges. However, what interested Borges in general was not so much the content of dreams as the dream itself, as a kind of framework for a new and heightened existence. The thinking and storylines in Borges’s poems, short stories, and essays are structured by dreams enveloping dreams, to the point where new realities are produced. And Piranesi — through De Quincey — is a progenitor of the compositional structures perfected by the Argentinian author.

Borges, however, extracts a new and what may ultimately be called a modern dimension from the compositions. In 1947 he published a short story, “The Immortal,” which evokes an ominous setting. The Palace of the Immortals in Borges’s tale is a terrifying place, built by and for human beings doomed to live forever. After entering the palace, traversing its caverns, descending a ladder, and making his way “through a chaos of squalid galleries” the protagonist concludes: “I am not certain how many galleries there were; my misery and anxiety multiplied them.” The emotional basis underpinning and generating such a structure derives from Piranesi, mediated through De Quincey, as the architect and writer Cristina Grau points out in her book on Borges and architecture. Borges, however, adds a dimension that is crucial in the history of Piranesi in the modern age, and that Grau never addresses: In Borges’s interpretation, Piranesi’s labyrinths of stairs and passages indicate not only a space but also a time prolonged with no end in sight. An architecture unfolding according to no coherent plan corresponds to a life that simply goes on and consequently has lost all meaning. To the infinite spatial sequence, which the “Carceri” seemed to codify, Borges adds an infinite temporal one.

The added dimension entails a subtle shift of architectural typology as well. Even more devious than a building that has no exits, like a prison, is a building with exits that lead nowhere, like a labyrinth. In Borges’s world, the Piranesian edifice becomes an analogy of life itself.

In “Chronicles of Bustos Domecq” (1967), Borges and his co-author Adolfo Bioy-Casares created the character of Bustos Domecq, the fictional writer of a series of essays that aim to capsize accepted truths. The ironic dedication, “To those three forgotten greats — Picasso, Joyce, Le Corbusier,” invites the reader to imagine a world in which these icons of modernism exerted no influence at all. On that cue, the book draws up alternative routes through the 20th century, including its architectural history.

In the essay “The Flowering of an Art” Bustos Domecq acts as mouthpiece for Borges’s dislike of modernist architecture and of Le Corbusier in particular. Borges never took to modernism. “The cubes of Le Corbusier never interested me,” he admitted on one occasion; on another, he lamented the atrocities committed by Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright. Although he was quick to exonerate Wright (recalling his own visit to the Guggenheim Museum in New York), no pardon was in store for Le Corbusier. On the contrary, the essence of Le Corbusier’s philosophy, the house as a machine for living, is the target in “The Flowering of an Art,” which celebrates a non-habitable architecture, in a parodic inversion of functionalist discourse. We are introduced to “Adam Quincey,” the fictitious author of a “short and badly printed” 1937 study, “Towards an Uncompromising Architecture.” The title paraphrases Le Corbusier’s classic manifesto from 1923 but a couple of “quotes” from Quincey’s “book” outline the somewhat opposite ideal of an architecture “not subject to the demands of inhabitability”: “Le Corbusier speaks of the house as a machine for living — a definition which seems less applicable to Taj Mahal than to an oak tree or to a fish.”

The name Adam Quincey, too, is a calculated part of the rhetoric. “Adam,” as scholar Ricardo Romera Rozas observes in a book on Borges and Bioy-Casares, alludes to Piranesi’s English patron and friend, Robert Adam, whereas “Quincey” of course refers to Borges’s muse, the inexhaustible dream-monger among the British Romantics. It is impossible to envision a greater contrast than the one that exists between Le Corbusier’s housing machines and De Quincey’s imagined palaces. From within the reality of a modernist architecture, Borges unwinds an opposite reality, drawing on modernism’s apparatus, references, terminology — a Trojan horse of dreams unleashed in the midst of functionalist facts.

In the second example of inhabitable architecture, Piranesi himself makes an entry, guised as a modernist, although a subversive one. In Borges’s and Bioy-Casares’s inverted history of the modern age, Bustos Domecq now evokes “Alessandro Piranesi,” architect of the so-called “Great Chaotic of Rome” erected in the late 1930s:

This noble edifice […] consisted essentially of truncated bridges, of spiral stairways that gave access to impenetrable walls, of balconies to which entrance was impossible, and of doors that opened either into pits or into high, narrow rooms from whose ceilings soft armchairs and comfortable double beds hung upside down.

It requires little imagination to see how the Great Chaotic expands on the “Carceri,” as if the architecture conveyed by the prints was the only rational solution to the needs of the 1930s. Parodying the sensationalist tone of modernist discourse, the (fictive) journal Architectural Forum proclaims the edifice “the first concrete example of the new architectonic conscience.”

In the persona of a fictive 12th-century architect, then, the 18th-century engraver reappears as a figurehead in Borges’s crusade against modernism. The ironic pairing of Le Corbusier and Piranesi is interesting because it reflects an identical pairing in architectural theory at the time, prompted by a similar revolt against modernism. In “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” (1966), issued the year before Borges’s Chronicles of Bustos Domecq, American architect Robert Venturi undermines the stern functionality associated with the Swiss architect by describing the Villa Savoye with the exact same phrase that he reserves for one of Piranesi’s impossible structures.

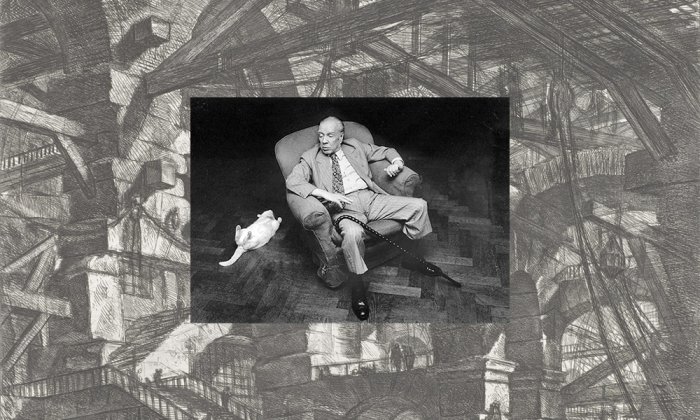

The Argentinian author drew inspiration from De Quincey’s Piranesi visions but I believe he also drew inspiration from Piranesi’s prints themselves. In the short story, “The Circular Ruins” (1941), Borges describes a derelict temple in which humans may dream up tangible realities, including other humans. At the end of the story, the narrator discovers that he too is a mirage conjured by an earlier dream-monger: “With relief, with humiliation, with terror, he understood that he too was a mere appearance, dreamt by another.” The buildings that enable this dreaming are described as “broken,” circular temples — temples “long ago devoured by fire, which the malarial jungle had profaned and whose god no longer received the homage of men.” On the wall of the living room of Borges’s apartment in Buenos Aires was an impression of Piranesi’s rendering of the temple of the god Canopus at Hadrian’s Villa (now believed to have been a nymphaeum) from Vedute di Roma, which depicts half of a circular structure, a giant, ruined hall, with its remaining half a gaping void. (The identification of the print in Borges’s apartment was made by Cristina Grau. In an interview with Borges for The Paris Review in 1966, the journalist Ronald Christ noted several unidentified etchings by Piranesi on the wall in Borges’s office in the Biblioteca Nacional in Buenos Aires.)

We will never know if Borges had this structure in mind when he conceived of the short story’s “dream-factory,” but it is likely. In any event, an architecture of “dreams” that allows for a surreal duplication of the self seems taken out of De Quincey’s recasting of Piranesi’s universe as dreamlike and highlights the uncertain states of existence that Borges’s characters share in. “Not to be a man, to be the projection of another man’s dream, what a feeling of humiliation, of vertigo!” — Borges’s main character exclaims. Borges, the observer of details, may even have noticed the enigmatic figure in the corner of Piranesi’s print who may be seen to “create” the entire scene — buildings and people included.

Victor Plahte Tschudi is Professor in Architectural History at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and the author of “Baroque Antiquity: Archaeological Imagination in Early Modern Europe” and “Piranesi and the Modern Age,” from which this article is adapted.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.