The phrase, “Don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time” is often hurled at people who have criminal records.

But the “time” of a person’s punishment often extends beyond prison walls and follows a person home. People with criminal records who have paid their debt to society frequently have a hard time getting housing — which can make them less likely to stay out of prison, by perpetuating a revolving door of housing instability, poverty, addiction, arrest, imprisonment and release.

Two recent reports underscore the importance of housing in reducing the cycle of incarceration. One, published by the Prison Policy Initiative, argues that giving people housing that isn’t tied to whether a person stays sober or gets help with mental health conditions gives them the stability they need to address life crises and makes them less likely to wind up back behind bars.

The other, published by Duke Law’s Wilson Center for Science and Social Justice, offers a slew of recommendations to make it easier for people returning home from prison to acquire a place to live.

“We know that homelessness and involvement in the criminal legal system can be cyclical and interrelated. Experiencing homelessness can make someone more likely to be involved in the criminal legal system and involvement in the criminal legal system can make someone more likely to experience homelessness,” said Wilson Center Policy Director Angie Weis Gammell. “Ensuring access to housing improves lives and reduces the likelihood of initial or repeat involvement in the criminal legal system.”

The Wilson Center policy brief suggests policymakers repeal zoning laws that make it harder for people with low and moderate incomes to obtain housing, revise public housing authority policies so they better align with federal standards for giving formerly imprisoned people access to housing, enact policies that reduce barriers the formerly incarcerated face in getting private housing, and institute interventions that meet individuals’ needs and meet them where they are at.

“Formerly incarcerated individuals face unique challenges in securing housing,” said Wilson Center Behavioral Health Policy Analyst Megan Moore. “Addressing their specific needs is crucial for ensuring housing access and stability overall as well as for ensuring the success of our returning community members.”

The consequences of homelessness and imprisonment disproportionately impact people of color, with each compounding issue perpetuating racial inequities. The Wilson Center report cites research showing Black people who have the same criminal records as white people are less likely to get callbacks for jobs. Similarly, the report notes, homeless rates are about 50% higher for Black people with criminal records compared to white people with records.

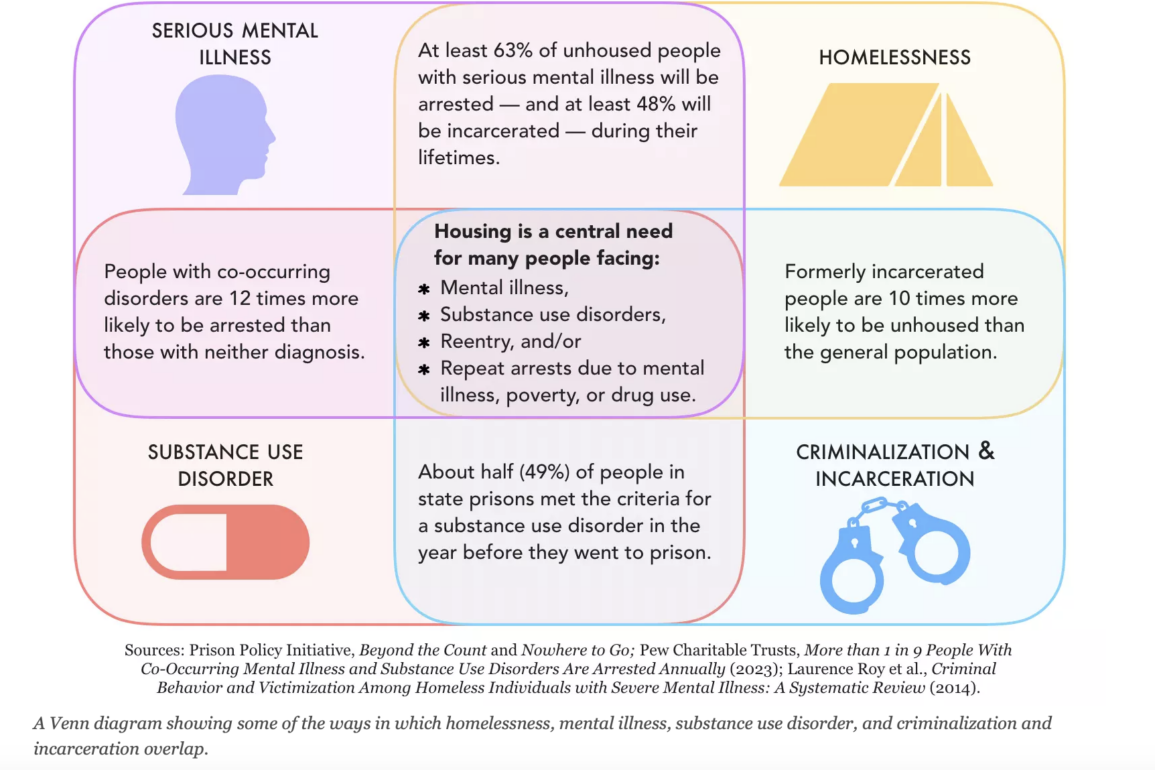

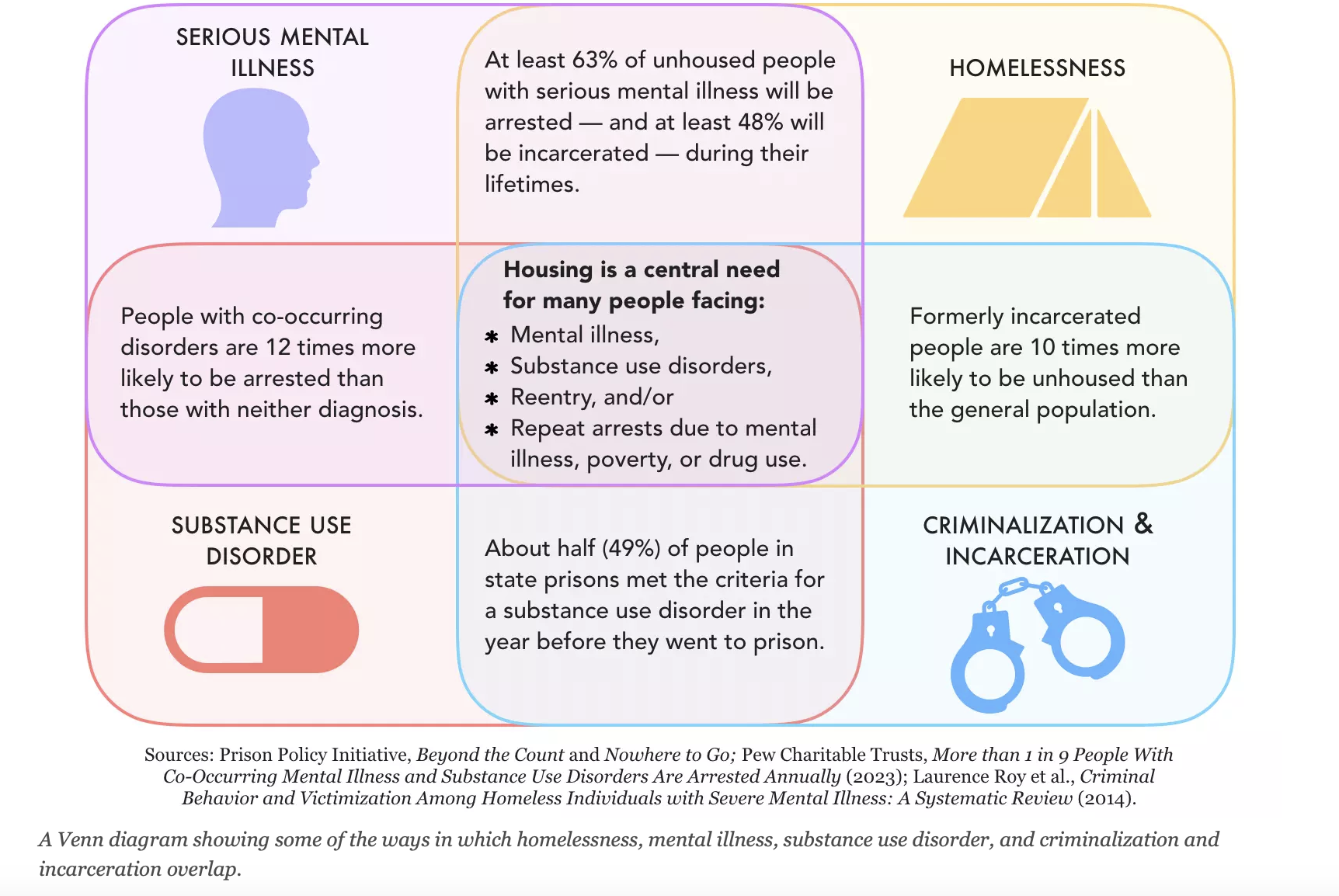

The Prison Policy Initiative briefing, meanwhile, examines the ways long-term housing can help people most at risk of going to prison: those with mental health conditions, substance use disorders or who are homeless. Reviewing more than 50 studies and reports, researchers argued that ending housing insecurity is a critical tool to reduce the number of people in jails and prisons.

“People caught in cycles of incarceration and homelessness are not all alike; they have different pathways to those experiences as well as a range of needs,” wrote Brian Nam-Sonenstein, senior editor and researcher at PPI. “But housing is one special factor that can stabilize multiple aspects of a person’s life at once.”

Where the two reports intersect is the concept of “Housing First,” an approach to homelessness that puts housing access as a first step in attaining stability, rather than something people should work toward. Those programs give people permanent supportive housing along with voluntary mental health treatment.

These policies are different from “Treatment First” and recovery housing models, which often require abstinence from drugs and alcohol as a condition for tenancy.

“For many years, housing policy was dominated by moralistic views of homelessness, which held that people just needed to take matters into their own hands and pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Drug use and mental illness were deemed character flaws and personal weaknesses, incompatible with housing or employment, and total sobriety and participation in treatment were required to receive what few services were available,” Nam-Sonenstein wrote.

The Wilson Center report cites a number of studies that suggest a Housing First model is often better for vulnerable people. One review, from 2020, found that Housing First programs decreased homelessness by 88% compared to Treatment First models. It also cites another study that found Housing First programs are about more than a roof over someone’s head: after two years, 86% of people in one such program in New York City were still housed and spent 40% less time in jail. Each person’s crisis health care costs were also $7,000 lower.

Click here to read the Wilson Center brief, and here to read the report from the Prison Policy Initiative. Here are some important numbers from both:

More than 500,000 – Number of people across the nation who live in homelessness

21% – Percentage of people experiencing homelessness who have a severe mental illness

16% – Share who suffer from chronic substance abuse

63% – Percentage of people experiencing homelessness and who have a serious mental illness who will be arrested at some point in their lives

48% – Share who will spend time behind bars

45% – Percentage of adults across the U.S. who have been diagnosed with a serious mental illness and have a substance use disorder.

12 – Number of times more likely those with both mental health conditions are likely to be arrested than people who don’t have either diagnosis

49% – Percentage of people in state prisons across the U.S. who meet the criteria for having a substance use disorder

10x – Rate of homelessness among formerly imprisoned people compared to the general population

One-third – Fraction of people in North Carolina prisons who have been homeless at some point in their lives, primarily because they couldn’t get a job, had a prior criminal conviction and struggled with substance abuse

27% – Unemployment rate for people who have been released from prison, five times higher than the national average

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.