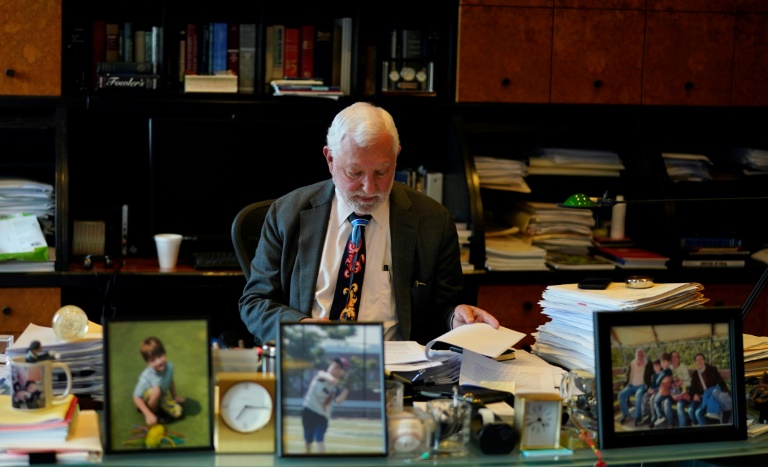

Judge Jed Rakoff says the US government failed to impose meaningful punishments on senior bankers involved in the 2008 financial crisis

TIMOTHY A. CLARY

US officials took a victory lap last month to commemorate their response to the 2008 financial crisis, pointing to $36 billion in fines as proof that banks have been held accountable.

But to US District Judge Jed Rakoff, who has criticized the Department of Justice (DoJ) for not criminally prosecuting senior bankers, such fines amount to an “easy cop-out” failing to achieve justice or discourage future chicanery.

“I don’t think it has a meaningful deterrent effect,” Rakoff told AFP as he reflected on the government’s enforcement record 15 years after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

“For the company, it’s a cost of doing business,” Rakoff said.

Rakoff bases this assessment in part on his 15 years in corporate law before being named to the bench.

The corporate defendants Rakoff represented made a “huge distinction” between financial penalties and prison time, seeking to avoid the latter at all costs because they’d “heard how terrible (prison) is,” he recounted.

“And so it follows from that, if you are fairly confident that, even if you don’t get away with it, the worst that will happen is your company will pay a lot of money, then you’re much more ready to go and do it,” said Rakoff.

He added that he wasn’t familiar enough with the details to comment on the bank failures earlier this spring that spurred emergency actions by the Federal Reserve and other regulators.

“To me, it’s a matter of simple morality,” Rakoff said. “Companies do not commit crimes in the moral, intentional sense. It’s individuals within the companies who make the decisions that ‘we’re going to do the wrong thing here, because it’s going to make our company a lot of money.’

“And those are the moral failings that need to be punished.”

Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in 2008, helping to ignite the global financial crisis

NICHOLAS ROBERTS

Consistently going soft on corporate criminals puts at risk the reputation that US markets “are among the most honest in the world and the most reliable,” Rakoff said.

“And when you have fraud that goes unprosecuted over time, it tends to undercut that confidence. And that is a serious, I think, problem for the United States.”

Judge Jed Rakoff, a senior judge for the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, says prosecuting CEOs involves a painstaking process

TIMOTHY A. CLARY

Appointed to the US District Court for the Southern District of New York by former President Bill Clinton in 1996, Rakoff is known for publicly taking on major judicial dilemmas more than colleagues.

He garnered attention in 2002 when he issued a ruling that found the death penalty unconstitutional, a decision that was quickly overturned on appeal.

Rakoff emerged as a critic of the government’s enforcement approach to the 2008 crisis, blocking a $33 million Securities and Exchange Commission settlement with the Bank of America.

In a scathing ruling, Rakoff in September 2009 dismissed the case as a “contrivance designed to provide the SEC with the facade of enforcement, and the management of the bank with a quick resolution of an embarrassing inquiry.”

While Rakoff later approved a modified settlement, citing the need for judicial restraint, he won praise as a rare check on Wall Street at a time of public rage against Big Finance.

After consulting court officers, Rakoff in 2014 began publishing essays questioning the enforcement response to the financial crisis, and in 2020 he authored a book critiquing the US justice system and addressing issues such as mass incarceration.

The DoJ last month announced that Swiss-based investment bank UBS would pay $1.4 billion to settle US charges that it defrauded investors in the sale of mortgage-backed securities.

The DoJ’s original complaint quoted a UBS mortgage official as referring to a pool of loans as “a bag of sh[*]t,” and another employee as calling a group of loans “quite possibly better than little beside leprosy spores.”

The UBS case marked the final major settlement under a DoJ-led working group established in 2012. The DoJ cited $36 billion in civil penalties as bringing accountability to “those who break the law and undermine the well-being of American families,” said an agency press release.

But Rakoff, a former federal prosecutor, likened such fines to a slap on the wrist — a retreat from the prosecutions in the early 2000s of top executives from Enron, Worldcom and other companies.

Limited resources explain some of the change, with DoJ focusing more on terrorism cases after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, Rakoff said.

A bigger issue is a shift in strategy. Prosecuting CEOs involves a painstaking process that typically requires charging people lower in the company and getting them to cooperate to catch a big fish.

“But those are hard cases to make,” Rakoff said. “They take a long time and sometimes you won’t be able to prove it in the end.”

By contrast, it may take six months to get a settlement, and “you can have a big splash in the papers: ‘Today Bank X pled guilty to a criminal offense and paid $5 billion.'”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.