In 2018, Congress passed and then-President Donald Trump signed into law the bipartisan First Step Act, a sweeping criminal justice reform bill designed to promote rehabilitation, lower recidivism, and reduce excessive sentences in the federal prison system. Lawmakers and advocates across both political parties supported the bill as a necessary step to address some of the punitive excesses of the 1980s and 1990s.

The First Step Act includes a range of sentencing reforms which made the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactive, enhanced judicial discretion, created earned time credits, increased good time credits, reduced certain mandatory minimum sentences, and expanded the safety valve that allows persons with minor prior convictions to serve less time than previously mandated.

The First Step Act also seeks to expand opportunities for people in federal prisons to participate in rehabilitative programming to support their success after release. The law aims to produce lower odds of recidivism by incentivizing incarcerated individuals to engage in rigorous, evidence-based rehabilitation and education programming. In exchange and based on a favorable assessment of risk to the community, they may earn an earlier opportunity for release to community corrections.

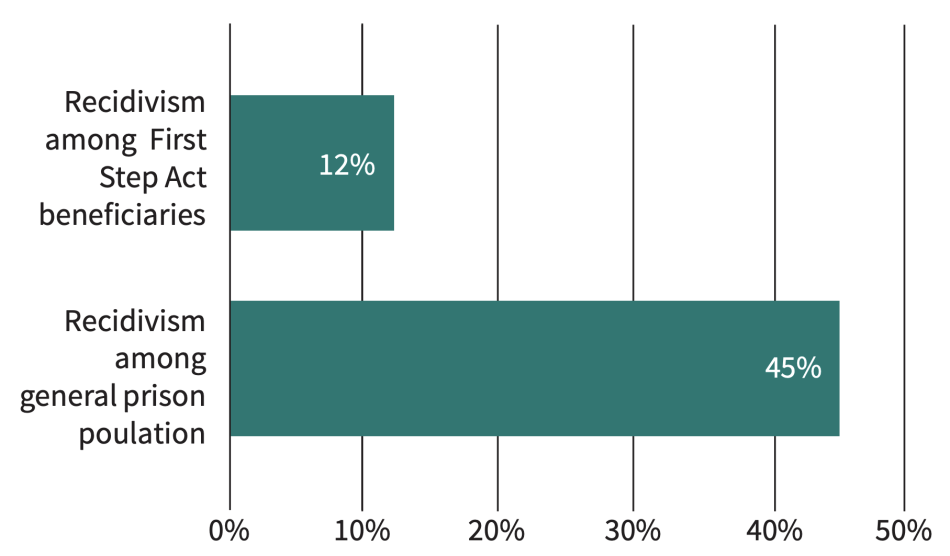

The Department of Justice (DOJ) reports promising results thus far. The recidivism rate among people who have benefitted from the law is considerably lower than those who were released from prison without benefit of the law. Among the nearly 30,000 individuals whose release has been expedited by the First Step Act, nearly nine in every 10 have not been rearrested or reincarcerated. This 12% recidivism rate lies in stark contrast to the more typical 45% recidivism rate among people released from federal prison.

Figure 1. Recidivism Outcomes in the Federal System Over a 3-Year Period

Source: U.S. Department of Justice. (2023). First Step Act annual report.; U.S. Government Accountability Office (2023). Federal Prisons: Bureau of Prisons should improve efforts to implement its risk and needs assessment system.

The majority (58%) of people released because of the First Step Act were serving time for a drug trafficking offense. Within this group, 13% have been rearrested or reincarcerated since their release. Comparatively, 57% of people released from state custody for a drug trafficking conviction recidivated within three years.

This brief describes why reforms included in the First Step Act have been deemed necessary to advance a fairer federal sentencing system and reduce the size of the federal prison population.

Why Reform was Necessary

The First Step Act is the result of many years of advocacy, negotiations, and compromise from a broad constituency of supporters that stretched from the White House to the prison corridors. As the name defines, it was intended as a first step toward unwinding the harms of mass incarceration at the federal level.

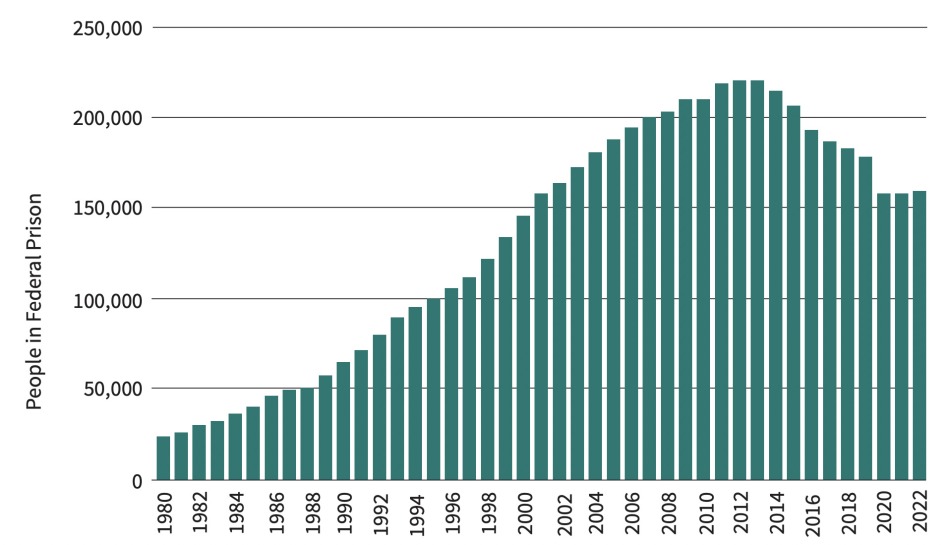

Due in large part to a series of draconian federal policies beginning with the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 and continuing with a range of misguided policies into the 1990s, the size of the federal prison population multiplied six-fold before beginning to fall in 2014.

A substantial portion of the federal prison growth was due to harsh penalties for drug offenses. In 1980, sentences for drug offenses accounted for 47% of the total admissions to federal prisons; by 1991, 86% of new federal sentences were for drug offenses. Indeterminate sentencing was replaced with mandatory minimums, three strikes laws, and the abolishment of parole.

The impact of these policies fell disproportionately on people of color, especially Black Americans, whose representation rose sharply in the federal prison population over this time. At the same time that harsh sentences were favored, prison administrations mostly abandoned the notion that rehabilitation and education programming while imprisoned would lead to lower reoffending rates on release, despite strong evidence to the contrary. Congress’s funding shortfalls also contributed to programming cutbacks.

The First Step Act was designed to be a multi-pronged solution to some of the most vexing problems of the federal prison system. The law expands opportunities for individuals to pursue rehabilitation and education, authorizes a range of early release mechanisms for eligible individuals to return to their families and communities, and makes retroactive the provisions of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 to reduce the disproportionate impact of especially harsh drug laws.

Figure 2. Federal Prison Population, 1980 to 2022

Source: Bureau of Prisons BOP: Population statistics. Accessed July 25, 2023.

Outcomes To Date

Expansion of Prison Programming and Education

The First Step Act authorized the expansion of rehabilitative and educational opportunities and incentivized eligible individuals to complete such programming. Between 2022 and 2023, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) expanded participation in evidence-based programs and promising, prosocial activities by 35%. Available programming, however, is still often inadequate to meet the needs of incarcerated individuals and the goals of the First Step Act. Just over 2,000 people in federal prison earned a GED or equivalent certificate in 2021 which, while nearly double that from 2020, is still quite low. The wait list for literacy program instruction in the BOP is over 28,500 people long.

Expedited Release

As mentioned at the outset, the DOJ reports that between 2019 and early 2023, approximately 30,000 people have been released from federal prison before their original release date as a result of the First Step Act’s reforms. Though a complete accounting of the particular components of the law responsible for these releases has not been published, the BOP reports the following figures on its website as of July 2023:

- 4,560 people have been released via compassionate release;

- 7,239 people are serving the final portion of their sentence at home via the Act’s “home confinement” provisions; and

- 4,000 people have been released through retroactivity of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010.

Compassionate Release

The First Step Act allows individuals who present extraordinary and compelling circumstances, such as severe illness and/or old age, and who pose little risk to the community, to bring their compassionate release applications directly to a federal judge 30 days after filing a petition with the BOP. Compassionate release was available before 2018, but infrequently used because of its poor design and implementation challenges., Section 603 of the Act amended section 3582(c)(1)(A) of title 18 to authorize “defendants” (i.e., imprisoned people) to file a motion for compassionate release “after the defendant has fully exhausted all administrative rights to appeal a failure of the Bureau of Prisons to bring a motion on the defendant’s behalf or the lapse of 30 days from the receipt of such a request by the warden of the defendant’s facility, whichever is earlier.”)) The ability for individuals to personally petition the court is a substantial departure from the previous policy, which mandated that only the BOP director could file a motion on behalf of an individual. This rarely occurred. In a 2016 report, the Office of the Inspector General chastised the BOP for its remarkably low grant rate: only 3% of compassionate release applications were granted in that year. Similarly low grant rates have been reported by the US Sentencing Commission. From 2013 to 2017, the BOP received 5,400 requests for compassionate release and approved only 6%. Taking an average of 4.5 months to issue a decision on these applications proved deadly, as 5% of the applicants died while waiting to learn the outcome of their plea.

The First Step Act rightly amended this segment of the law and since its passage, 4,560 people have returned to their communities and families because of it. In its first year, 2019, 55 people were granted release. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread through prisons, this part of the law became a lifesaving device for many, helping to preserve the health of elderly and medically vulnerable individuals. The grant rate among people applying for compassionate release rose to 27% in the height of the pandemic. The Commission found that for individuals granted compassionate release in 2020, reductions in sentence were significant, with an average reduction of nearly 5 years or nearly 40% of an individual’s sentence. Following this rise, the grant rate fell to 12% and 13% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Still, a larger overall number of qualified people have been released because of expansion of this mechanism.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.