In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis suspended a second prosecutor. In Texas, activists are trying a new way to get rid of D.A.s they dislike.

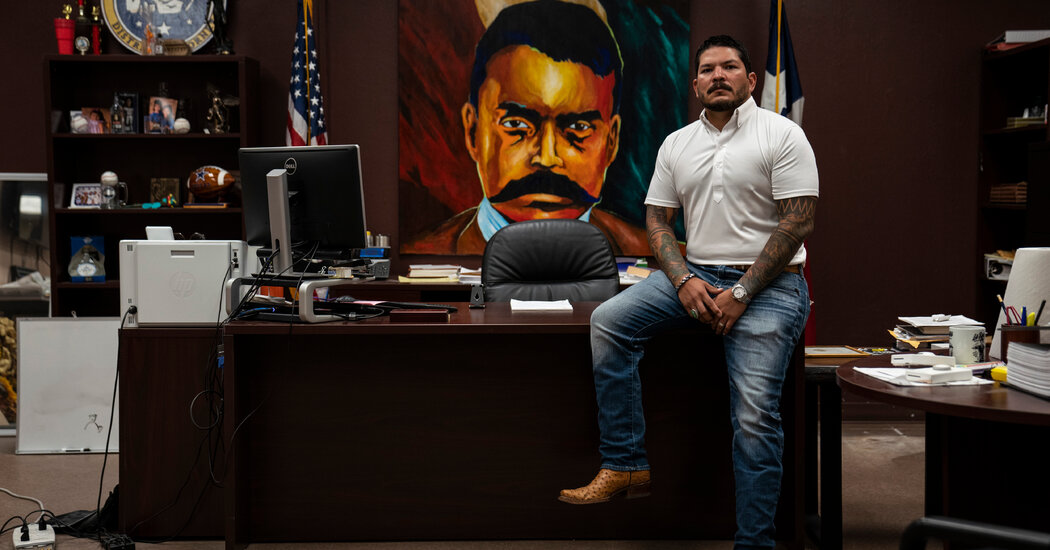

When he was elected district attorney in Nueces County in 2016, Mark A. Gonzalez stood out even among a growing class of progressive Democratic prosecutors: a former criminal defense attorney with tattoos across his body, including one reading “Not Guilty,” whose name appeared in a Texas state police database of registered gang members.

Once deemed “the most unlikely D.A. in America,” Mr. Gonzalez was one of the first prosecutors in Texas to encourage police to ticket people, rather than arrest them, for a range of minor offenses. He made his office friendlier to defense lawyers. And he won re-election.

Now, Mr. Gonzalez is facing a sudden and unexpectedly serious challenge: a trial next month to remove him from office over allegations of “gross carelessness” and “gross ignorance” of his duties, the result of a petition filed by a conservative activist and backed by the county attorney, a Republican.

The removal effort is one front in an expanding campaign by conservatives across the country to limit the power of Democratic prosecutors who have promised to reform the criminal justice system, or else to oust the prosecutors altogether.

Most recently, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida suspended the elected prosecutor in Orlando, Monique H. Worrell, on Wednesday over her handling of violent crime cases. He did the same last year to the top prosecutor in Tampa, who had said he opposed prosecutions for abortion or gender-related health care offenses.

Prosecutors have also faced removal by other means. In Pennsylvania, Republican lawmakers led a vote last year to impeach Larry Krasner, who is serving his second term as Philadelphia’s top prosecutor. In St. Louis, Kim Gardner stepped down in May after legislators introduced a bill that would have allowed the governor to appoint a special prosecutor in her place, and after the state attorney general filed a lawsuit seeking to remove her.

More than two dozen bills have been introduced in 16 states to limit prosecutors’ power, mostly in Republican-controlled states, according to an analysis by nonprofit groups opposed to the legislation. Several of those bills have become law, including in Tennessee, Georgia and Texas.

Despite attacks on their policies and attempts to blame them for rising crime, progressive prosecutors have continued to win many elections. Several have fended off challengers and been re-elected by wide margins, including Mr. Krasner, who has succeeded so far in fighting off the attempt to remove him through impeachment. New reform-minded D.A.s have been elected in Minneapolis, Des Moines and a host of other cities.

But in some cases, they have also faced political headwinds. A coalition of voters in San Francisco, including independents, moderate Democrats and Republicans, voted last year to recall the city’s district attorney, Chesa Boudin, midway through his first term. Mr. Boudin had eliminated cash bail and promised to reduce incarceration, but found himself under mounting criticism over persistent property crime and open drug use in the city.

Attempts to rein in prosecutors hinge on legal distinctions that vary from state to state, but at their heart, they are a battle between executive discretion and prosecutorial discretion, said Carissa Byrne Hessick, director of the Prosecutors and Politics Project at the University of North Carolina. The Supreme Court has generally been protective of prosecutorial discretion, she added.

The Republican-dominated Texas Legislature passed a law this year limiting the discretion of “rogue” district attorneys. The new law, signed by Gov. Greg Abbott, was aimed at Democratic prosecutors in cities like Dallas, San Antonio and Austin who pledged, after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in the Dobbs decision last year, not to pursue abortion cases.

Mr. Gonzalez, whose office is based in Corpus Christi, also signed the pledge. That was listed among the reasons he should no longer hold office in the removal petition that was filed against him on January by a resident of Nueces County, a purple corner of coastal South Texas.

“If D.A.s or county officials of any political party act with disregard for their oath of office, nullify duly enacted law, or otherwise commit official misconduct, they should be held accountable with all lawful means,” said Colby Wiltse, the resident who filed the petition.

Mr. DeSantis has invoked similar arguments for removing the two Florida prosecutors.

“Prosecutors have a duty to faithfully enforce the law,” Mr. DeSantis said in announcing this week that he had suspended Ms. Worrell. “One’s political agenda cannot trump this solemn duty.”

But some prosecutors, who are usually afforded considerable discretion, have chafed against narrow definitions of their jobs. Most understand their role to be to seek justice, not just convictions, including by deciding which cases to bring and which to dismiss, and in some instances, by helping to exonerate people who are wrongfully imprisoned.

In Georgia, one Republican prosecutor complained that a newly established oversight board could potentially punish him for his policy of not prosecuting adultery, which is technically still a crime in the state.

In the case of Ms. Worrell, Mr. DeSantis suspended her soon after two Orlando police officers were shot and wounded this month by a gunman who had posted bond on a previous offense. Some law enforcement officials said the man should have been held in jail as he awaited trial.

Judges, not prosecutors, ultimately decide whether to set bond, though they typically do so with input from prosecutors and other parties.

Ms. Worrell called Mr. DeSantis’s actions “political shenanigans,” and in an interview on Wednesday, she said that others should be concerned: “I think every Democrat is in jeopardy.”

Unlike efforts to remove prosecutors in Florida and other states, the process in Texas grew out of an unusual application of a state law that allows any citizen to seek the removal of a county official, like a district attorney, on the grounds of incompetence, official misconduct or intoxication.

Mr. Wiltse said in an email that he had become concerned about crime in Corpus Christi and the surrounding county, and learned about the law that allowed him to petition for the removal of Mr. Gonzalez, whose policies toward people accused of offenses, Mr. Wiltse believed, were too lenient.

Mr. Wiltse is the Texas state director of Citizens Defending Freedom, a Florida-based conservative group that has spread rapidly since its creation in 2020. Among its goals are mobilizing local people to push for conservative policies on education and elections, and against progressive prosecutors. A lawyer from the group assisted Mr. Wiltse with his petition.

A few weeks after filing the petition against Mr. Gonzalez, Mr. Wiltse told a Republican state senator that the approach could provide a model. “If this goes through and this is successful, this could be the springboard to holding other corrupt district attorneys accountable by we the people,” he said.

But the petition to remove Mr. Gonzalez could not have gone forward to a trial without the support of the county attorney, Jenny Dorsey, a former prosecutor who worked under Mr. Gonzalez.

The petition, which Ms. Dorsey exercised her power to amend, included accusations that Mr. Gonzalez has frequently been absent from work, that he failed to supervise his prosecutors, that he dismissed large batches of cases in order to secure state and federal grants, and that he has used his personal Facebook page to promote a country store that he owns with a partner. Ms. Dorsey removed mention of the pledge not to prosecute abortion offenses, since no such cases had yet emerged.

“It’s there for a reason,” Ms. Dorsey said of the removal process during an interview in July in her offices at the county courthouse. “There’s nothing political about ignorance and carelessness.”

Mr. Gonzalez denied any wrongdoing. “We’re dismissing cases because it’s the right thing to do,” he said.

Over breakfast at a Corpus Christi restaurant, Mr. Gonzalez said that for years, he had been subjected to searches at airports because of his affiliation with the Calaveras, a motorcycle club he joined and whose members he had represented as a defense lawyer. He said that only relatively recently — well after being elected district attorney — did he believe his name had been removed from a statewide gang database, and noted that he had passed through airports recently without extra scrutiny.

“I don’t think we’re a gang, and I don’t think anyone in the club is part of a gang,” he said.

If the trial leads to Mr. Gonzalez’s removal, his replacement would be appointed by Mr. Abbott. Mr. Gonzalez said that whatever the outcome, he would not run for another term next year.

Shaila Dewan, Patricia Mazzei and Frances Robles contributed reporting.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.