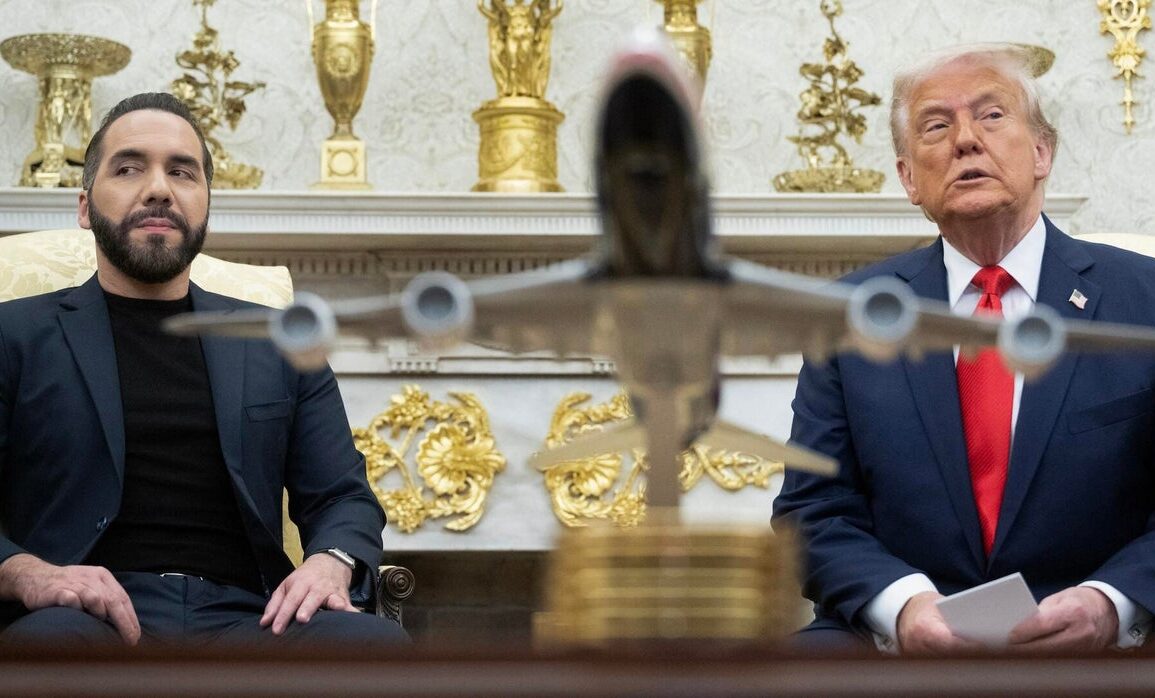

Washington — President Trump’s administration is studying current laws to see if they are able to send U.S. citizens who commit violent crimes to prisons in foreign countries, the president said this week in his Oval Office meeting with El Salvador’s tough-on-crime President Nayib Bukele.

But sending U.S. citizens abroad to be incarcerated raises serious constitutional concerns, say legal scholars who focus on constitutional and criminal justice matters.

“I think it would raise many very profound constitutional problems, and I think there are good reasons why no prior administration has tried to do this for prisoners in the criminal system,” said Daniel Kanstroom, director of the Rappaport Center for Law & Public Policy at Boston College.

“Sending American citizens to serve their sentences in a prison outside of the United States would violate the U.S. Constitution,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior director of the Brennan Center’s Justice Program. And sending U.S. citizens to El Salvador specifically “would be a violation of the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution” prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment, she said.

Asked Monday if his openness to sending criminals abroad includes U.S. citizens, Mr. Trump told reporters, “If they’re criminals and if they hit people with baseball bats over the head that happen to be 90 years old, and if they rape 87-year-old women in Coney Island, Brooklyn, yeah, that includes them.”

Mr. Trump said the U.S. can send criminals abroad for “less money” than housing them in the U.S. The president told Bukele he’ll need to build “about five” more facilities to house “homegrown” criminals — meaning American citizens — in El Salvador. The Trump administration has sent hundreds of migrants whom they allege without concrete evidence are gang members, although some of those cases are playing out in court.

On Fox News Monday night, Attorney General Pam Bondi was asked whether the idea is something the U.S. is allowed to do.

“These people need to be locked up as long as they can, as long as the law allows,” Bondi said. “We’re not going to let them go anywhere. And if we have to build more prisons in our country, we will do it.”

Mr. Trump didn’t specify which violent crimes would make people eligible for being sent abroad. “I’m talking about violent people, I’m talking about really bad people,” he said Monday.

Brendan Smialowski / AFP

How experts say imprisoning U.S. citizens abroad is constitutionally questionable

Kanstroom said much depends on how such an incarceration program could be implemented, but there are some obvious constitutional questions.

“Among the constitutional problems, you have obvious problems under the Fifth Amendment in terms of due process,” Kanstroom said. “You have problems under the Eighth Amendment, that it might be deemed cruel and unusual punishment. You have problems under the 14th Amendment, that it might challenge equal protection of the law for citizens.”

Clark Neily, senior vice president for legal studies at the Cato Institute who specializes in constitutional and criminalization issues, said other countries don’t have even the protections for prisoners that U.S. prisons do. It’s hard to see how the U.S. would conduct oversight of those facilities, Neily said.

“The Eighth Amendment does prohibit cruel and unusual punishment, and certainly there are countries where you can imagine that the conditions of confinement would fall below even the very low floor that the Supreme Court has established,” Neily said. “That it would include things like views of corporal punishment, which some countries still do.”

Eisen detailed the conditions in El Salvador, specifically at the Center for the Confinement of Terrorism, or CECOT. The Trump administration has sent 238 men there whom it alleges are affiliated with gangs. Inmates at CECOT aren’t allowed outside or given access to education, she said. A 2022 U.S. State Department report on human rights in El Salvador found prisons there often have food shortages, inadequate sanitary conditions, and lack medical services.

“Certainly, all we know about this prison in El Salvador suggests it’s an extremely cruel place,” said David Super, a professor of law and economics at the Georgetown University Law Center.

Incarcerating U.S. citizens abroad would be almost certainly unconstitutional because “they wouldn’t be able to, presumably, get habeas corpus, or be able to file petitions for habeas corpus,” said Stanford Law professor Bernadette Meyler.

Habeas corpus means recourse for challenging one’s conditions of or reasons for confinement.

Further, under Article One of the Constitution, only Congress can write the statutes that determine punishment for federal crimes.

“That wouldn’t be constitutional, at least, absent some congressional authorization,” Meyler said — and even then, there are constitutional concerns, she said.

“There is no law that calls for punishing criminals by shipping them out of the country,” Georgetown Law’s Super said.

Sending U.S. citizens abroad to be incarcerated is an issue that harkens back even further than the U.S. Constitution, Super said. The Declaration of Independence cites King George III’s objectionable actions — “and one of those is transporting people over the seas who were accused of crimes,” Super said.

“So our country was founded on the premise that this is not accepted,” Super said.

Boston College’s Kanstroom pointed out that when former President George W. Bush set up Guantanamo Bay in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, “U.S. citizens were specifically exempted from that.”

Could the U.S. send citizens who are charged but not yet convicted abroad?

Holding U.S. citizens abroad who are merely accused, but not convicted, would pose even more concerns, although it’s not clear from the president’s language whether that’s off the table. The U.S. has seemingly sent non-citizens who are charged but not convicted to El Salvador.

If the U.S. did send citizens to be held abroad before a trial conviction? “Absolutely unconstitutional,” Kanstroom said. “….If that starts to happen, our constitutional democracy has been completely lost.”

Americans should pay attention to what the federal government is doing because it’s a slippery slope that could apply to political enemies and other citizens, Kanstroom said.

“There are a lot of people who have been saying, ‘Well, deportation doesn’t affect me because I’m a U.S. citizen,'” Kanstroom said. “And now they say that this was an experiment. And the experiment starts with noncitizens. And then the idea starts with, why not try it against citizens? And it could first be naturalized citizens who would be naturalized and then possibly deported … And it could be dual nationals, and at that point, why restrict it to them?”

The logistical hurdles of incarcerating U.S. citizens abroad

People convicted of serious crimes still have a right to counsel and a right to access the judicial system, Kanstroom and Neily said. Those things would be, logistically speaking, nearly impossible to do from a foreign country.

“How would they have access to counsel, and how would they have access to the U.S. judicial system?” Kanstroom posed.

And it’s not clear that a country like El Salvador would allow U.S. visitors into their facilities. Sen. Chris Van Hollen, speaking from El Salvador on Wednesday, said he was not allowed to meet with Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the man the Trump administration initially said in court that they mistakenly sent to El Salvador for incarceration. The White House has since stood by his deportation to an El Salvadoran prison. The Supreme Court has said the Trump administration must facilitate his return to the U.S., but El Salvador’s president says he won’t release him.

It’s also unclear how the U.S. government would guarantee the return of citizens upon completing their sentences.

“You’d run into a problem of, how would the person get back?” Kanstroom said.

Kanstroom also said holding U.S. citizens abroad might not save the federal government money, given the additional procedural steps the government would have to take.

“I think it’s extremely unlikely that it would save money,” Kanstroom said. “I think it would cost more in terms of process and you, know challenges, and just the logistics would be extremely difficult to manage. People do have a right to family visits; they do have a right to meet with their lawyers. All of that would have to be arranged in some way.”

Of the over 1.9 million people incarcerated in the U.S., only about 208,000 are in federal prisons and jails, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. And of those 208,000, the Prison Policy Initiative says only 11,000 are convicted of violent crimes. The rest of the country’s incarcerated people are housed in local jails and state prisons, which are outside of federal control.

Incarcerating U.S. citizens abroad might violate one of Trump’s own laws

Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior director of the Brennan Center’s justice program, said the president’s proposal isn’t only “illegal” under the Constitution but under one of his signature first-term laws.

The First Step Act, signed into law by Mr. Trump in December 2018, requires the Bureau of Prisons “to house inmates in facilities as close to their primary residence as possible, and to the extent practicable, within 500 driving miles” of their residence. The reason behind that was to facilitate family visitation, the Brennan Center’s Eisen said, and allow inmates to see clergy and other community members.

“No matter how you do the math, prisons in El Salvador are not within 500 driving miles (nor even 500 flying miles) of any part of the United States,” Eisen wrote in a piece for the Brennan Center last month.

There are U.S. citizens who are incarcerated abroad, Kanstroom said — the U.S. military has prison facilities in Germany and Korea for soldiers convicted in the military system. But those places are “quite meticulously governed by U.S. personnel,” Kanstroom said.

“Assuming that they’re talking about a person who has a full jury trial and then could be sentenced to a to a facility abroad, it seems to me the only possible way to do that, and even then it would raise a lot of problems, it would have to be under complete U.S. control,” Kanstroom said.

In short, Kanstroom said, it’s hard to imagine a legally defensible way to send U.S. citizens abroad for imprisonment.

“Even if it were set up in the most meticulously pristine way imaginable, which seems extremely unlikely to me, you still have very profound constitutional problems here in terms of forcing a U.S. citizen out of the country,” Kanstroom said.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.