A plane carrying scores of Venezuelan prisoners touched down in El Salvador on Sunday, cementing a landmark deal with the Trump administration to house suspected gangsters abroad.

The prisoners, alleged to be associated with the Tren de Aragua and MS-13 gangs, were deported even after a U.S. federal judge blocked their removals, and the government is yet to supply any detail of their supposed gang affiliation.

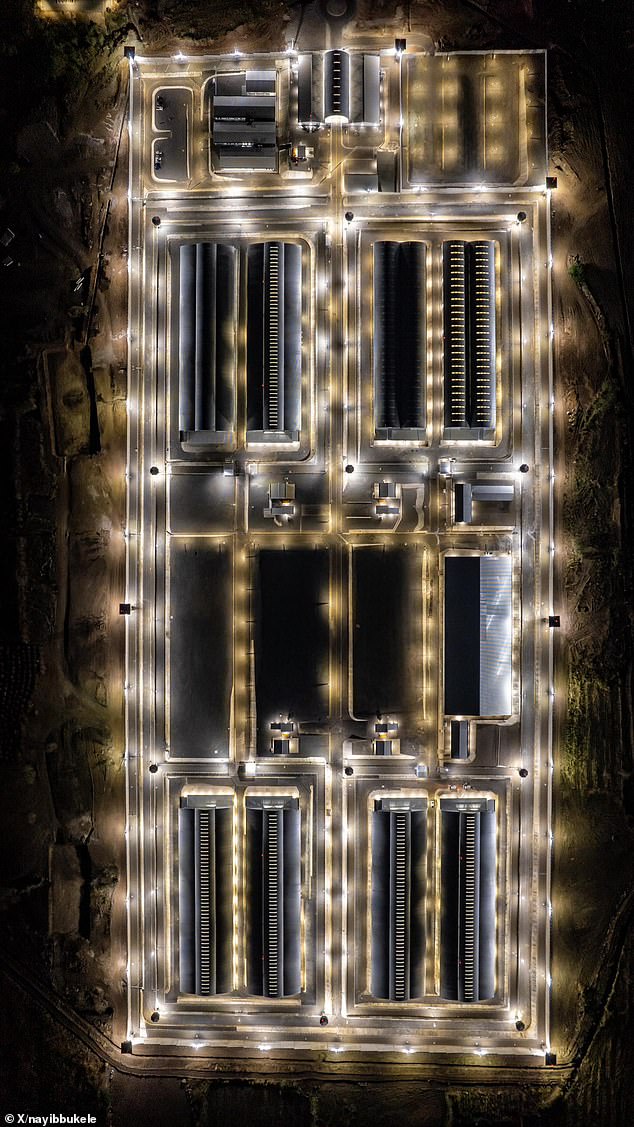

More than 200 Venezuelans will now be transferred to the supermax Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT) prison in Tecoluca, a sprawling complex for thousands of hardened gangsters and a symbol of Salvadoran president Nayib Bukele’s harsh crackdown on gang violence since it opened in 2023.

For the strongman president of El Salvador, the $6mn deal with the United States is an opportunity to show the world the brutal efficacy of his repressive ‘State of Exception’ regime – an excess of the growing autocratic trend turning its back on liberal democracy.

For the prisoners, a ‘black hole of human rights’ awaits, according to monitoring groups. At least 363 people have died in Salvadoran prisons since the policy came into effect, rights group Cristosal told MailOnline, many citing ‘horrific overcrowding, disease, systematic denial of food, clothing medicine, and basic hygiene’.

The jewel in the crown, CECOT has been heralded by Bukele as a superweapon in the war on gang violence. Confined to cells of 70 for all but 30 minutes a day, prisoners are held in dire conditions, forbidden from going outside or having visitors, and are made to sleep on steel cots without mattresses in cramped conditions.

As Venezuelans alleged to be gang members arrived in El Salvador to join some 20,000 of the country’s most hardened criminals, MailOnline looks at the conditions inside Bukele’s CECOT fortress.

The CECOT maximum-security prison was built in 2023 in the context of the ‘State of Exception’, a national policy ostensibly aimed at tackling sprawling gang violence with a rigorous crackdown on alleged gang members.

Bukele has identified the worst offenders as members of the MS-13 and Calle 18 gangs – groups that emerged in the wake of the 1979-1992 Salvadoran Civil War, a twelve-year conflict between the US-backed government and a coalition of left-wing guerilla groups backed by Cuba’s Fidel Castro and the USSR.

As refugees fled north to the United States for a better life, many sought protection from other local gangs and joined factions. When the war ended, the conflict followed them home. A wave of attacks in recent years have seen the deaths of scores of civilians on Salvadoran soil.

Extortion, drug trafficking and brutal killings became commonplace, with non-combatants among those directly targeted by the gangs.

With this came support for a more sweeping response from the state. Bukele declared a ‘State of Exception’ in March 2022, and commissioned CECOT soon after to be opened in January 2023.

The ‘State of Exception’, a concept outlined by Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt in the 1920s, is a right enshrined in the constitution that allows the state to temporarily suspend certain guaranteed rights under special circumstances in order to restore public order.

Rights groups say the policy’s use in El Salvador has seen thousands of arbitrary detentions, torture and hundreds of deaths in state custody, as well as the use of rape against women and children, and the forced disappearances of those deemed ‘internal enemies’ of the state.

CECOT is the most vivid symbol of the new order. At the base of a towering volcano, and miles from civilisation, huge concrete walls separate some 20,000 of the country’s most violent prisoners from the rest of society.

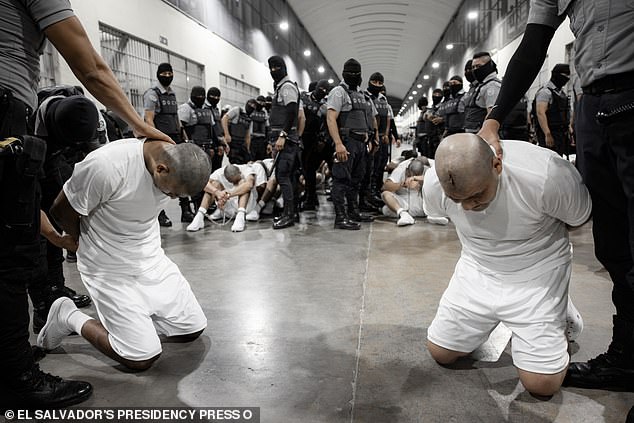

Soon after construction emerged polished photos of 2,000 of the country’s most hardened criminals subjugated, humiliated and in chains inside a plain and utilitarian prison complex in Tecoluca.

‘El Salvador has managed to go from being the world’s most dangerous country, to the safest country in the Americas,’ Bukele said at the time.

‘How did we do it? By putting criminals in jail.’

Inmates at CECOT endure some of the most stringent restrictions seen in modern prisons.

Cells, designed to hold 65 to 70 prisoners, are stark and devoid of basic comforts. Each cell has two toilets and two sinks to share between all. Inmates collect drinking water from a plastic barrel like animals.

At full capacity, ‘each inmate will have just 0.6 square metres within shared cells’, the FT estimates.

Prisoners can only leave their cramped cells once a day – for thirty minutes of exercise inside the prison’s large central corridor.

They sleep on metal cots without mattresses or pillows and are ground down on a strict diet of rice, pasta, tortillas, beans, and cream, with meat expressly prohibited.

To guard the prison, a crack team of 800 prison staff kitted out with riot gear patrols the hallways. Inmates are deprived entirely of their right to privacy, watched 24 hours a day with CCTV cameras.

The few areas in the prison carved out for respite – break rooms, dining halls, a gym – are reserved for the guards. No books are allowed.

Despite the cramped conditions, isolation poses a challenge for those expecting never to leave. Inmates cannot receive visitors, and judicial hearings only take place via video link.

While prisoners are regularly frisked and checked for contraband, the prison has a jammer to stop information getting out.

Due to the broader lack of transparency, the wellbeing of prisoners is underreported. But according to CBS, prisoners who need medical attention are treated within the modules, ‘so no prisoner ever leaves the premises alive’.

Staff are aware of the ‘problems’ inside CECOT, and boast of overcrowding cells.

The BBC asked the director last year what the capacity of each cell was.

‘Where you can fit 10 people, you can fit 20,’ he replied, ‘appearing to smile from behind his anti-Covid mask’.

While no expense was spared building the colossal prison, the facility has no windows, fans or air conditioning, meaning temperatures soar upwards of 95F, or 35C.

Most of those living inside the prison expect to die there. There is no hope of rehabilitation or a return to civilised society with good behaviour.

This is something accepted by prison staff; director Belarmino Garcia told the AFP news agency that the inmates were ‘psychopaths who will be difficult to rehabilitate’.

‘That’s why they are here, in a maximum security prison that they will never leave,’ he said.

On the rare occasion that prisoners are allowed to speak to the press, they are careful in how they relay their experience.

Inmate Marvin Vazquez, a member of the MS-13 gang, told CBS News during a visit this month: ‘We murdered a lot of people, and this is the consequence of what happened to us, is like the Titanic.

‘That we were a big and strong gang. But we got hit with the iceberg.’

‘We try to act strong in the day and cry in the nighttime,’ he said.

A 41-year-old man, nicknamed Sayco, told AFP that he regretted his past, but knew that ‘we are in a maximum security prison where we know there is no way out’.

Marvin Medrano, serving a 100-year sentence for two murders, told AFP he regretted his ‘bad decisions’ and hoped his son would take a different path.

‘I have lost my family, we’ve lost everything in prison,’ Medrano told the visiting reporters.

As observed by the Associated Press: ‘There are no programs preparing them to return to society after their sentences, no workshops or educational programs. They are never allowed outside.

‘The exceptions are occasional motivational talks from prisoners who have gained a level of trust from prison officials.

‘Prisoners sit in rows in the corridor outside their cells for the talks or are led through exercise regimens under the supervision of guards.’

The lack of educational or vocational programs means that prisoners have no chance of growth or atonement.

The absence of such programmes has been criticised as a violation of the inmates’ rights to education and rehabilitation.

By contrast, even Britain offers prisoners ‘programmes and interventions’ that ‘aim to change the thinking, attitudes and behaviours which may lead people to reoffend’.

In most cases – 74.5 per cent – successful rehabilitation programmes allow prisoners to reintegrate and becoming contributing, working members of society again.

For prisoners in El Salvador’s CECOT, the choice between reoffending and redemption does not exist.

When Human Rights Commissioner of El Salvador, Andrés Guzmán, visited the notorious prison early on, he insisted the inmates are ‘in good condition and their human rights are being respected’.

But rights groups have since compared the conditions in the prison as something similar to the concentration camps used by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis.

Miguel Sarre, a former member of the United Nations Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture, told the BBC that the prison appeared to be used to ‘dispose of people without formally applying the death penalty’.

Monitoring groups have also described the prison as a ‘black hole for human rights’.

They say it fits into the wider picture of a ‘State of Exception’ by which the government has overseen the ‘return of torture, forced disappearances and arbitrary detentions established practically as state policy’.

Noah Bullock, director at Cristosal, told MailOnline that the lack of transparency surrounding the prison crackdown has made it hard for rights groups to fully report on the conditions inside.

Testimonies gathered by Cristosal from former prisoners across El Salvador, detained during the State of Exception, ‘decried horrific overcrowding…disease, systematic denial of food, clothing, medicine, basic hygiene’, he said.

‘Cristosal has also documented credible evidence of rape and sexual assault against women and children detained under the State of Exception.

‘These intentionally harsh conditions are combined with acts of systematic physical torture that have led to the deaths of at least 363 people,’ he said, noting that the figure could be higher.

The group reported only last summer that 261 people had died in El Salvador’s prisons since the crackdown began in March 2022.

The Socorro Juridico Humanitario rights group estimates that almost a third of those detained under the State of Exception are innocent.

Confounding matters, journalists have allegedly been threatened with prison for news media that reproduces or disseminates messages from the gangs, alarming press freedom groups.

While the U.S. government once warned that the State of Exception had seen ‘arbitrary arrests’ and ‘undermined due process’ while exacerbating ‘difficult conditions in overcrowded prisons’, the decision to deport more than 200 suspected Venezuelan criminals implies an attitude shift under the new Trump administration.

The CECOT ‘mega-prison’ in Tecoluca has become a symbol of El Salvador’s harsh crackdown on gang violence since it was built in 2023.

After decades of unchecked violence, some citizens still welcome a radical move that promises to keep streets clean and safe.

But while the prison’s harsh conditions may serve as a deterrent to criminal activity, they also raise profound ethical and human rights concerns.

Locals warn that people are being arbitrarily designated ‘internal enemies’ of the state and systematically rounded up to be caged in conditions unbefitting of any living creature.

Once accused, they are completely unprotected against the ‘repressive power’ of the state, and may soon find themselves sentenced to tens or hundreds of years in a brutal penitentiary with no contact with the rest of the world.

When Guantanamo Bay opened in 2002, the reaction from Europe was one of disgust.

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben described the indefinite detention of noncitizens in the U.S. as a ‘state of exception’ with the potential to turn a democracy into a totalitarian state.

Two decades later, a new political landscape has allowed CECOT to stand in El Salvador in the context of another state of exception, this time with an implied blessing from a U.S. administration willing to send suspected criminals to its cells.

Rights groups will jostle to decide how history will remember the Salvadoran prison experiment. For the prisoners inside, all there is to do is wait.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.