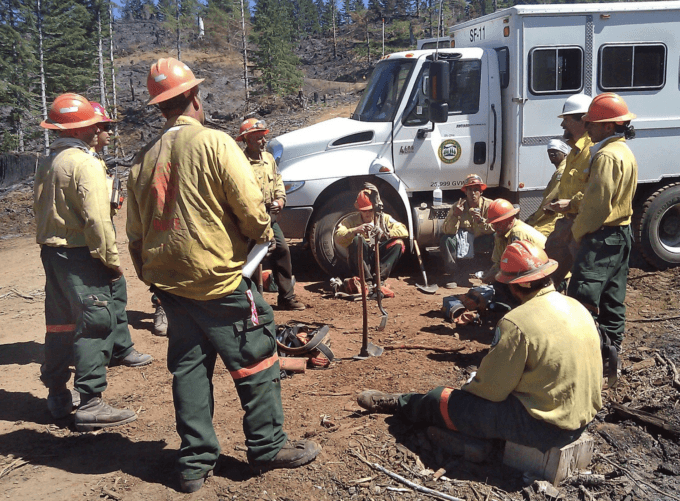

Inmate fire crew from South Fork Forest Camp. Photograph Source: Oregon Department of Forestry – CC BY 2.0

Why does American society remain so deeply implicated in the enslavement of Black Americans? Slavery was never abolished in the United States, and today it enjoys widespread support among both Republicans and Democrats. Almost 800,000 people are subject to the conditions of prison slavery, but this estimate is almost certainly low, as the lack of reliable data means that it “excludes people confined in local jails or detention centers, juvenile correctional facilities, and immigration detention facilities.” This system, supported and perpetuated by both halves of the ruling class, is an extension of the country’s history of racism and chattel slavery, a way to reinstitute slavery within a legal framework that loudly insists it has been abolished.

The new slavery is a shameful mark on our country’s pretenses to respect for human rights and the dignity of every human being, the latest chapter in a story of race-based hierarchy and domination. When slavery was formally abolished, a major loophole was left in place, one that would help race-based slavery survive to the present day. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in December 1865, inscribes the Emancipation Proclamation’s abolition of slavery into the country’s supreme source of law, but it does not contemplate a total end to slavery within the nation’s borders. Rather the amendment carves out a fateful exception to the prohibition of slavery:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction [emphasis added].

Slavery is perfectly legal and permissible as long as the enslaved are deemed criminals, which allows prisons to completely dispense with any protections for prison workers. It goes without saying that this exception to the general rule against slavery creates a major incentive to criminalize the mere existence of Black Americans, to use the criminal justice system to create a permanent pool of free labor. If prison slavery is not, on its own, the primary cause of the mass incarceration crisis besieging Black bodies, then billions of dollars’ worth of free labor every year nonetheless remains a powerful force in the service of a racist, two-tier system of “justice.” And indeed this incentive problem has done its work within the American social system, propelling and insulating a system of mass incarceration that recalls and recreates the race-based slavery that so deeply defines the country’s history.

All available evidence shows that the longer one spends in prison, the more likely they are to end up back in the system after they’re back in society. But here is “the great irony of our American criminal justice system.” Today, we imprison huge numbers of people and the prison sentences have grown longer—“thus our system of mass incarceration all but assures high rates of recidivism.” The scale of mass incarceration in the United States is “unparalleled historically” and the shame of the country on the global stage as an egregious violation of accepted human rights. Today, some 2 million people are held in America’s prisons and jails (the majority, about 1.2 million of them, in the prisons), and they live in some of the harshest conditions of abuse and neglect. The data on the country’s sadistic penchant for mass incarceration are startling: in 1972, the rate of imprisonment was about 93 people per 100,000, but by 2009, it was seven times that number, and in the decade between 1985 and 1995, the prison population grew by an average of 8 percentage points every year. Black Americans are highly over-represented in the contemporary prison system; last spring, the Prison Policy Initiative found that “the national incarceration rate of Black people is six times the rate of white people” (emphasis in original). As we shall see, once they are locked up, Black people are far more likely to be subjected to inhumane treatment and even to conditions regarded as torture under international human rights law.

The criminalization of Black existence is a time-honored tradition in the United States. After the formal abolition of slavery, the policing, court, and prison systems have become the primary means through which Black Americans are deprived of their freedom and relegated to second-class political and economic status. Voting in California this past fall saw voters reject Proposition 6, which would have eliminated a provision in the state’s constitution that permits involuntary servitude as punishment of incarcerated people. It would also have prevented the state from continuing to discipline those in prisons who refuse to work. It seems that America’s voters, even in blue states, remain enthusiastic about slavery.

Those enslaved in America’s prisons “are paid very little (between 13 and 52 cents an hour on average)—if at all—and are excluded from the basic rights and protections afforded to most workers.” Many U.S. states offer no compensation at all for work undertaken while in prison. These are the people who do some of the most dangerous and unpleasant work there is, from fighting massive forest fires and processing poultry to disposing of biohazardous waste, often without appropriate safety equipment, having been stripped of even the most minimal legal protections.

Totally captive and vulnerable, American prisoners are subject to a form of super-exploitation—they can be forced to do anything for any or no pay. They have no right to refuse work. But every year they produce more than $11 billion in economic value through the goods they help to manufacture and the services they provide. Those who do refuse to work under these slavery conditions are subject to severe punishment, often torture, as in the case of solidary confinement. The United Nations has said that indefinite or prolonged solitary confinement of longer than 15 days is a form of torture and thus a violation of international law. More than 3 of every 4 prisoners report that refusals to work are met with additional punishments such as “solitary confinement, denial of opportunities to reduce their sentence, and loss of family visitation, or the inability to pay for basic life necessities like bath soap.”

In 2022, the ACLU and the University of Chicago Law School’s Global Human Rights Clinic released a report detailing the findings of one of the most comprehensive studies of the U.S. prison system to date. Their study gives us one of the clearest pictures we have of the massive human rights crisis ongoing in the country’s prisons, combining a thoroughgoing review of government data with surveys and interviews of over 100 prison workers (in California, Illinois, and Louisiana) and “65 interviews with key stakeholders including experts, formerly incarcerated individuals, representatives of advocacy organizations, academics, and leaders of reentry organizations across the country.” The investigation spanned a period from 2018 to 2022 and involved Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests in all 50 states. The study reveals that more than 4 out of 5 enslaved prison laborers work on “general prison maintenance, which subsidizes the cost of our bloated prison system,” meaning that the captive are forced to prop up their own enslavement.

Today, many states require all of their government bodies to purchase things like “furniture, cleaning supplies, printed materials, and uniforms” from the prison system. The ways in which the political class speaks of those enslaved in America’s prisons follows in an unbroken current of racist rhetorical strategies popular throughout the country’s history. The forced labor to which they are subjected is for their own good, instructing and edifying them, providing them a point of access to the superior white, Western mind and its culture. Though it is frequently advanced with the language of dignity and rehabilitation, this rationale is fatally undermined by the best evidence we have from inside the country’s prisons. Prison laborers report that the contemporary slavery to which they are subjected serves in fact to “degrade, dehumanize and further cripple incarcerated workers,” according to Global Human Rights Clinic Fellow and lecturer Mariana Olaizola Rosenblat.

Degradation and dehumanization are fundamental features of this system. In February 2024, both the DOJ Office of the Inspector General and the Government Accountability Office released comprehensive reports on the connected crises of widespread preventable death and continued, pervasive overreliance on solitary confinement. The Inspector General’s report looked at four types of preventable deaths: suicide, homicide, accident, and unknown factors. Over an 8-year period covered by the report, 344 people fell into one of these categories. The report shares its finding that “a combination of recurring policy violations and operational failures contributed to inmate suicides, which accounted for just over half of the 344 inmate deaths we reviewed.” Many of the policy violations and operational failures involved the subject of the GAO report, which was the follow-up on an earlier study that resulted in a number of recommendations. Last year’s report confirmed that the Bureau of Prisons had failed to deliver on “54 of the 87 recommendations from two prior studies on improving restrictive housing practices.” The GAO report also observed the startling racial disparities in the use of restrictive housing. Though they were 38 percent of the total Bureau of Prisons population, Black prisoners were 59 percent of the restrictive housing placements; whites were 58 percent of the total population and 35 percent of these placements. The connection between solitary confinement and the most severe mental health issues is clear in the available data, as more than half of the inmates who committed suicide were in solitary confinement at the time. It is hardly a coincidence that the brutality of this system is today at its worst for Black people in the South. A January 2025 report from the Economic Policy Institute points out that in the South “incarceration rates are the highest, prison wages are lowest, and forced labor arrangements bear the most striking resemblances to past forms of convict leasing and debt peonage.” The report shows that states in the American South “incarcerate people at the highest rates in the world.” If we treated U.S. states as countries for the purposes of the global ranking, 30 of them (plus the U.S. as a country) would find a place at the top of the global incarceration rate list. Only El Salvador tops several Southern states, and only El Salvador, Cuba, Rwanda, and Turkmenistan “rank higher or alongside these 30 states” in the world.

Proper maintenance of the prison labor pool has become a major public policy priority, and it is often the rationale for avoiding measurable improvements to prison conditions. As a 2023 note in the Harvard Law Review pointed out, then-Attorney General of California Kamala Harris “met heavy criticism” for advancing this kind of reasoning as a way to fight in court against the enforcement of the Supreme Court’s historic decision in Brown v. Plata. Against all of the available evidence, California argued that overcrowding was not in fact the source of the constitutional violation. As Justice Kennedy pointed out at oral argument, “Overcrowding is of course always the cause.” While prisoners were sitting in their own feces and dying in record numbers, Harris and her office were insistent that extreme levels of overcrowding in the country’s largest (by population and economy) and richest state should not be directly addressed. California prisoners were commiting suicide at a rate twice that of the national average.

The factual record in the case also clearly demonstrated that alternatives to prison were both more effective at reducing recidivism and less expensive. Harris and her office “filed motions that were condemned by judges and legal experts as obstructionist, bad-faith, and nonsensical, at one point even suggesting that the Supreme Court lacked the jurisdiction to order a reduction in California’s prison population.” For Kamala Harris, as for the rest of the political class, upholding the constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment was less important than maintaining a proper stock of slaves to fight fires and perform other brutal and dangerous jobs. The example of California here underscores just how easy it has been for the “progressive” quarters of the U.S. political establishment to forsake the clearest and most egregious constitutional and human rights violations with no real criticism from their supporters. Understanding these contemporary political realities requires that we confront American history.

Very few among white society in the South accepted either their defeat in the war or the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment as the final word on whether Black people were their rightful slaves. Without some system of labor super-exploitation, the entire social order and way of life would be upended. And although this was of course the real demand of abolition, that would not stand. Capital, dependent on free labor, had to find a way to replace the productive capacity of the freed slaves. A tidal wave of new legal and social strictures came in the wake of the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment, calculated to reinstate the second-class status of the Black population and concomitantly the exploitative economic system associated with it. New Black Codes imposed a comprehensive and draconian system of control and punishment for the crime of being Black on Southern soil. A form of racial capitalism continued from the slave economy.

Vagrancy laws were used to drive Southern Blacks both into low or unpaid work or else into the prisons, where slavery remained and remains perfectly legal. A complex new system of convict leasing arose in the place of traditional chattel slavery during reconstruction, with discipline and authority enforce brutally through “gang rapes, beatings and harassment of weaker cons,” through ranks of sub-bosses and “trusty shooters” who could be relied upon to eliminate noncompliant prisoners. W.E.B. Du Bois summarizes this state of affairs in his 1935 book Black Reconstruction: “The whole criminal system came to be used as a method of keeping Negroes at work and intimidating them. Consequently, there began to be a demand for jails and penitentiaries beyond the natural demand due to the rise of crime.” As Du Bois points out, prior to formal emancipation, Southern prisons held comparatively few people, the overwhelming majority of whom were white.

As the celebrated historian Gerald Horne put it, “They linked race and class. It’s not as if our ancestors were brought to these shores because people didn’t like us, because people despised us. They were brought to these shores for profit, to be an unpaid working class.” Contemporary elite discourse in the United States has largely attempted to understand slavery without reference to its class component, as an expression of racial hatred in an economic vacuum. Hubert Harrison wrote similarly that Black Americans “form a group that is more essentially proletarian than any other American group,” “brought here with the very definite understanding that they were to be ruthlessly exploited.”

It is impossible to understand lynching as an accepted cultural spectacle without confronting the question of economic class as the defining aspect of American racism. As even the lowest of the low in white society could partake in the sadistic killing of Black people, this dark ritual buttressed the rigid hierarchical structure of society at the time. Lynchings were the crystallized, concentrated expression of the brutal violence at the heart of the social order, which constructed whiteness in terms of the ability to dispose of Black bodies arbitrarily and at will. This expression of whiteness preempted the possibility of poor whites discovering their class solidarity with enslaved Blacks.

The perpetuation of slavery on American soil gives the lie to the ridiculous, ahistorical idea that the American economic system is something even somewhat like a “free market,” based on robust protection of individual liberty and rights. The capitalist system requires that there be masses of people who can be absorbed into a system of violent, programmatized deprivation. American capitalism continues to be predicated on domination and exploitation, the most severe forms of which still include forms of race-based slavery that, like their antecedents, are treated as legal and legitimate within our class hierarchy.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.